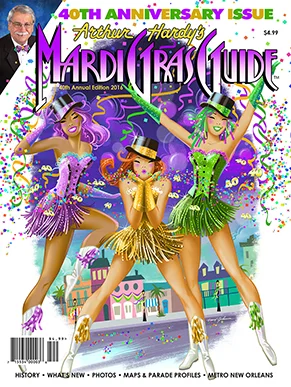

The History of Mardi Gras, by Arthur Hardy

Arthur Hardy is the World's Foremost Authority on Mardi Gras.

Hardy has written a number of books and publications on the subject of Mardi Gras, and publishes an annual Mardi Gras Guide, recognized as the official program to the event. This beautiful collector's edition program is included in every Mardi Gras Insider Tours Package. To check out Arthur Hardy's site and for more information on his works, please click here.

The History

The celebration of Mardi Gras came to North America from Paris, where it had been celebrated since the Middle Ages. In 1699, French explorer Iberville and his men explored the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico. On a spot 60 miles south of the present location of New Orleans, they set up camp on the river's West Bank. Knowing that the day, March 3, was being celebrated as a major holiday in France, they christened the site Point du Mardi Gras.

During the late 1700′s, pre-Lenten masked balls and festivals became common in New Orleans.

But Mardi Gras’ roots predate the French. Many see a relationship to the ancient tribal rituals of fertility that welcomed the arrival of Spring. A possible ancestor of the celebration was the Lupercalia, a circus-like orgy held in mid-February in Rome. The early Church fathers, realizing that it was impossible to divorce their new converts from their pagan customs, decided instead to direct them into Christian channels. Thus Carnival was created as a period of merriment that would serve as a prelude to the penitential season of Lent.

In the late 1700s pre-Lenten balls and fetes were held in New Orleans. Under French rule masked balls flourished, but were later banned by the Spanish governors. The prohibition continued when New Orleans became an American city in 1803, but by 1823, the Creole populace prevailed upon the American governor, and balls were again permitted. Four years later street masking was officially made legal.

The 1839 Parade consisted of a single float. Nonetheless, it was considered to be a great success, as the crowd roared with laughter as this somewhat crude float moved through the streets of the city.

In the early 19th Century, the public celebration of Mardi Gras consisted mainly of maskers on foot, in carriages and on horseback. In 1837, a costumed group of revelers walked in the first documented “parade,” but the violent behavior of maskers during the next two decades caused the press to call for an end to Mardi Gras. Fortunately, six New Orleanians who were former members of the Cowbellians, (a group that had presented New Year’s Eve parades in Mobile since 1831), saved the New Orleans Mardi Gras by forming the Comus organization in 1857. The men beautified the celebration and proved that it could be enjoyed in a safe and festive manner. Comus coined the word “krewe” and established several Mardi Gras traditions by forming a secret Carnival society, choosing a mythological namesake, presenting a themed parade with floats and costumed maskers, and staging a tableau ball following its parade.

The official Mardi Gras flag

After the Civil War, Comus returned to the parade scene in 1866. Four years later, the Twelfth Night Revelers debuted. This unique group made Carnival history at its 1871 ball when a young women was presented with a golden bean hidden inside a giant cake, signifying her selection as Mardi Gras’ first queen and starting the “king cake” tradition. A visit by the Russian Grand Duke Alexis Romanoff was the partial inspiration for the first appearance of Rex in 1872. The King of Carnival immediately became the international symbol of Mardi Gras. Rex presented Mardi Gras’ first organized daytime parade, selected Carnival’s colors — purple, gold and green, produced its flag, and introduced its anthem, “If Ever I Cease To Love.” On New Year’s Eve, 1872, the Knights of Momus also entered the Carnival scene. Several Carnival parades in the 1870s ridiculed the government in Washington D.C. and Carpetbagger Administration in Louisiana.

World War I Liberty Bond Parade on Canal Street

The popular Krewe of Proteus debuted in 1882 with a glittering parade that saluted Egyptian Mythology. The Jefferson City Buzzards, the grandfather of all marching clubs, was formed in 1890. The first black Mardi Gras organization, the Original Illinois Club, was launched in 1894. Two years later, Les Mysterieuses, Carnival’s first female group, was founded and presented a spectacular Leap Year ball.

The final year of the Century saw snow in New Orleans on Fat Tuesday, which fell on St. Valentine’s Day. Legend has it that Rex paraded with a frozen mustache!

Promotional poster for the Mobile Mardi Gras Carnival, February 26th & 27th 1900.

One of the first and most beloved krewes to make its appearance in the 20th Century was Zulu. Seven years before its incorporation in 1916, this black organization poked fun at Rex. The first Zulu King ruled with a banana stalk scepter and a lard can crown. While Rex entered the city via a Mississippi River steamboat, Zulu used an oyster lugger to plow up the New Basin Canal.

The new Century brought with it some difficult years. World War I canceled Carnival in 1918-1919, but Mardi Gras survived this struggle, along with the Prohibition of the Twenties and the Great Depression of the Thirties.

In 1934 Carnival festivities hit the West Bank of the Mississippi with the first Alla parade. Random truck riders were organized into the Elks Krewe of Orleanians in 1935. The Krewe of Hermes and the Knights of Babylon were organized in 1937 and 1939, respectively.

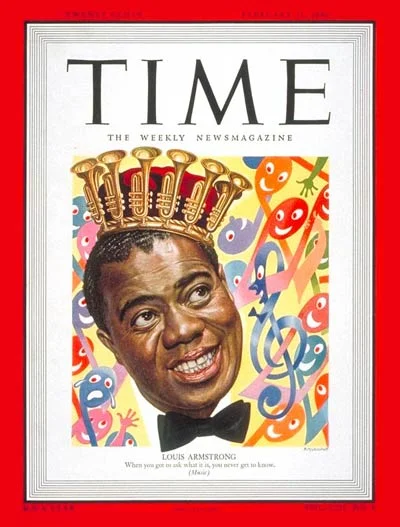

In the Forties a new spirit of Mardi Gras was ushered in, pausing only for the United States’ involvement overseas. Before World War II canceled four Carnivals, the first women’s parade graced the streets of New Orleans with the Krewe of Venus’ inaugural pageant in 1941. New Orleans’ favorite son, Louis Armstrong, returned home to ride as King of the Zulu parade in 1949. In honor of the event, Satchmo’s likeness made the cover of Time magazine.

TIME Magazine Cover: Louis Armstrong -- Feb. 21, 1949

The Fifties provided international publicity and continued expansion of Mardi Gras. Real royalty, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, honored the make-believe Monarchs of Merriment as they bowed to Rex and Comus at the 1950 Comus ball. The next year the Korean conflict canceled much of Carnival, but several krewes combined to form the Krewe of Patria, which paraded on Fat Tuesday. After nearly a century of mule-drawn floats, tractors replaced the faithful beasts. The decade also saw the formation of other krewes, including Zeus, the first suburban club, which paraded in Metairie.

The Sixties were characterized by turbulence and change. The early years saw the Greater New Orleans Tourist Commission try to convince the hippies that the title “Greatest Free Show on Earth” was not to be taken literally. The “Easy Rider” generation had City Hall worried, and rumors that the infamous Hell’s Angels were going to roll into town and crash Carnival had the entire town uptight. Nothing negative happened, and Carnival continued without incident.

Pete Fountain started his Half-Fast Walking Club in 1961 and it quickly became a hit with Fat Tuesday crowds. Thinking that the antics of the Krewe of Zulu were undignified, portions of the black community put pressure on the group. Its king resigned and the 1961 parade was almost canceled. Not only did Zulu survive, however, but by 1969, its parade was also a main attraction on Canal Street. Finally, just as the decade had begun with the historic introduction of the Rex doubloon, so did the period end with another landmark event — the start of the Bacchus organization. The krewe’s founders, feeling that the traditional Mardi Gras institutions had become static, wanted to attract national attention and make Carnival more accessible. In 1969, Bacchus shook the establishment by presenting the largest floats in Carnival history, by having a Hollywood celebrity ride as its king (Danny Kaye), and by presenting, in place of the traditional ball, a supper dance to which tickets could be purchased by both visitors and locals. These innovations proved immensely popular and were to be copied by several future carnival organizations in New Orleans.

Mardi gras coronation ball

New Orleans Mardi Gras parade passing down the 100 Block of St. Charles Avenue to Canal Street, 1930s

Carnival’s growth continued throughout the Seventies with the birth of 18 new parading krewes, and, ironically, the death of 18 others. More than one dozen clubs featured celebrities in their parades. Argus brought a Fat Tuesday parade to Metairie, and Endymion exploded into a super-krewe in 1974. A ban on parading through the French Quarter ended a 117-year tradition, and a moratorium of new parade permits put a temporary cap on expansion in Orleans Parish. The decade ended with a police strike in New Orleans, causing the cancellation of 13 Mardi Gras parades in Orleans Parish. Twelve parades rescheduled in the suburbs.

The decade of the 1980s saw the dawn of 27 new parades and the demise of 19. The Mardi Gras parade calendar shrank drastically in St. Bernard Parish, while in St. Tammany and Jefferson Parishes, Carnival continued to grow. By 1989, more than 600,000 people annually attended parades on the east and west banks of Jefferson Parish on Fat Tuesday.

mardi gras revelers of a time gone by

Feeling the need for better safety measures and more coordination of Carnival activities, the Mayor of New Orleans formed a Mardi Gras Task Force to study all aspects of the celebration. In 1987, Rex resurrected “Lundi Gras,” the customary Monday arrival on the Mississippi River which the group had enjoyed from 1874 to 1917. The traditional tableau ball, once an essential activity for all parading krewes, lost its popularity, with only about 10 of the 60-plus clubs still retaining a bal masque format by the decade’s end.

Doubloons lost some of their luster as several krewes stopped minting them. Krewe-emblemed throws of every imaginable variety gained popularity, however, with imprinted cups leading the pack.

Perhaps the greatest change in Mardi Gras in the 1980s was the tremendous increase in tourism during the Carnival season. Conventions which once had avoided New Orleans at Mardi Gras used the celebration as a reason to assemble here. International media attention was focused on Mardi Gras in the late 1980s, with camera crews from Japan, Europe and Latin America showcasing the festivities. Mardi Gras also became a year-round industry as more off-season conventions experienced the joys of Carnival when they were treated to mini-parades and repeat balls held in the city’s convention facilities.

Historians may one day record the decade of the Nineties as a pivotal one in Carnival history. While an in-depth economic impact study revealed that Mardi Gras’ annual economic impact finally neared the billion dollar mark, political intervention decreased the size and scope of the celebration. Shortly before the 1992 season, a New Orleans city ordinance was enacted that required all parading krewes to open their private membership. Comus, Momus and Proteus protested the government’s intrusion into their affairs by canceling their parades, while Rex opened it membership to blacks.

Eleven new parades debuted in the 90s, while 15 folded. The Krewe of Orpheus, led by Harry Connick Jr., was an instant hit and quickly assumed super-krewe status.

parade floats rolling down Saint Charles avenue

The birth of Le Krewe d’Etat and the Ancient Druids, plus the triumphant return of the Krewe of Proteus in 2000, were highlights as Mardi Gras marched on into the new millennium. The year was also the first when the economic impact of Carnival crossed the one billion dollar mark. The next year, the new female krewe of Muses debuted to an excited parade crowd.

The horrific events of September 11, 2001, impacted Mardi Gras by reducing the number of visitors in subsequent years.

In 2002, some 15 parades were pushed back one week to avoid a conflict with the rescheduled Super Bowl in New Orleans. In a hotly negotiated settlement, Orleans Parish krewes whose parades were displaced were reimbursed $20,000 each for their losses.

The first decade of the 21st Century may be remembered as a time of consolidation and improvement of the existing product rather than the addition of more and more parades. Citing a dramatic rise in the demand for city services — police, sanitation, emergency — local govenments sought ways to raise revenue and reduce costs. A moratorium on new parades in Orleans and Jefferson Parishes has been issued.

Arthur Hardy is the World's Foremost Authority on Mardi Gras.

Hardy has written a number of books and publications on the subject of Mardi Gras, and publishes an annual Mardi Gras Guide, recognized as the official program to the event. This beautiful collector's edition program is included in every Mardi Gras Insider Tours Package. To check out Arthur Hardy's site and for more information on his works, please click here.